Dr Norman

Claringbull

Psychotherapist

Counsellor

Psychologist

The Friendly Therapist

Call now for a free initial telephone consultation

Total confidentiality assured

In-person or video-link appointments

Private health insurances accepted

Phone: 07788-919-797 or 023-80-842665

PhD (D. Psychotherapy); MSc (Counselling); MA (Mental Health); BSc (Psychology)

BACP Senior Accredited Practitioner; UKRC Registered; Prof Standards Authority Registered

BLOG POST – Sept/Oct 2015

Posted on August 29th, 2015

HOW CBT WORKS

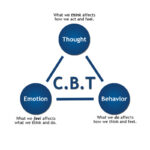

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy, (CBT), is based on a very simple concept. It is this – Cognitive-Behavioural therapists believe that how we think, (COGNITION) affects how we act, (BEHAVIOUR), and conversely, how we BEHAVE, (actions), affects how we THINK, (cognition). In other words, they claim that it is our individual ways of thinking and behaving that makes each of us who we are and what creates our individual ways of being.

If this is true, then it follows that if we have any psychological problems or emotional difficulties then they must have been caused by psychologically harmful errors in our established ways of thinking and behaving. Therefore, all we have to do in order to ‘cure’ our psychological ‘ills’ is to identify these errors and correct them. Of course, like any ‘Mr Fix It’ we need a work plan and so we need to find out what needs fixing, how to fix it, and how to keep it fixed? When CBT practitioners are trying to help their clients find answers to those three apparently simple questions, they have to keep in mind two important CBT principles

1. The first essential CBT principle this. Events, (each person’s experiences), are not important in themselves, it is how we think about or interpret those events that matters. It is our individual interpretations that make us react in the various ways that we do. For example, seeing someone with a gun is usually frightening, (COGNITION 1), and so we might run away, (BEHAVIOUR 1). However, seeing a police officer with a gun is much less frightening, (COGNITION 2), and so we probably won’t run away, (BEHAVIOUR 2). In other words, it is not the gun itself that is scary but our interpretation of what the gun means, (threatening/non-threatening?), that governs our reaction. It is our perceptions that influence how we think, feel, and act.

2. The second essential CBT principle is this. Feelings, emotions, and thoughts, (COGNITIONS), together with actions, behaviours and physical symptoms, (BEHAVIOURS), are all mutually interlinked and form our individual personality networks. Therefore, any change anywhere, large or small, in our behavioural/cognitive networks will reverberate throughout our entire system and inevitably cause changes.

COGNITIVE ERRORS:

When we get our thinking, (COGNITIONS), wrong then we can cause ourselves all sorts of psychological problems. A core role for a CBT therapist is to try and help clients to discover where their thinking is faulty. Only then can they be helped to put things right. Knowledge is empowering. We can get the wrong idea about ourselves or about what is happening to us in a number of ways. Here are two of the most important sources of error.

i) Negative Automatic Thoughts, (NATs)

We all have them. They are our habitual, (automatic), stereotypical ideas about ourselves: “I’m no good at practical stuff”; “People don’t like me”; “Whatever I do goes wrong”. NATs are all the putting-ourselves-down ways in which we routinely interpret, (often inaccurately), what goes on in our worlds.

ii) Core Beliefs, (CBs)

These are the fundamental ideas that provide the bedrock of our views about ourselves. A core belief that “I am fundamentally stupid” can underpin such NATs as “I’ll never be able to do crosswords”; “I can’t pass that exam”; “I won’t get that job”. Core beliefs tend to be located in the darker corners of our cognitive ‘storage systems’ and so they are often hard to locate, identify and change.

Either or both of these faulty cognitive processes, (NATs and CBs), contribute to our psychological problems. Their fundamental purpose is to influence how we regularly interpret, (or more accurately misinterpret), life’s events. It is the task of the CBT therapist to help clients to put right any such errors in their thinking. This is a process that psychologists call ‘reframing’.

BEHAVIOURAL ERRORS:

When we get our BEHAVIOURS wrong then that too can harm us. For example, people who have a long-term problem with anxiety may have learned to automatically behave in ways that keep their bodies in a high state of tension, (muscle stress, high pulse rate, over-breathing, and so on). This sort of long-term harmful behaviour will go on to affect long-term thinking and such a person is often feeling scared and worried, (generalised anxiety, phobias, obsessions, etc.). If they can learn to reduce these levels of harmful behaviour, (de-stress themselves), in some way, (relaxation therapy, yoga, meditating, exercising, etc., etc.), then it is very likely that their fears and worries will lessen as well. In other words beneficial changes in ways of behaving can create beneficial changes in ways if thinking.

AND FINALLY:

All this makes delivering CBT seem very easy. Simply correct bad thinking, (COGNITION), or remedy bad BEHAVIOUR and all will be well. However, in practice doing this is nothing like as simple as it sounds and that is why skilled therapists are needed.

At the beginning of this post, referring to the basic principles of CBT, I did say ‘if this is true’. I put it that way because a lot of psychotherapists, (and very many counsellors), take the view that CBT is a very inadequate response to their patients’ psychological disorders. CBT’s opponents argue that at best it only offers clients symptom relief and that it fails to address their underlying emotional and developmental concerns. Their argument is that even if CBT helps clients to feel better in the short-term, any such benefits are unlikely to be long-lasting. This supposed lack of therapeutic ‘staying power’, CBT’s detractors claim, is because according to them CBT is not ‘proper psychotherapy’.

Personally, I take the view that choosing, or not choosing, to use CBT as a therapeutic tool does not need to be an ‘either/or’ decision. In my psychotherapy practice, CBT and all the other mainstream modes of psychotherapy go hand in hand. That is how I prefer to work with my patients. Each patient is unique and so each patient’s treatment plan is a ‘one-off’. Therefore, I tailor my psychotherapeutic approach, (my treatment plan), to fit each patient’s individual needs. In other words, I give my clients the type of help that they need, when they need it. If they need CBT then so be it. When they need something different then I give them something different. If that sounds like a ‘best of all worlds’ approach to delivering psychotherapy then that’s exactly what it is. I’m quite happy to ‘pick and mix’. Whatever works – works!